NOTES ON THERAPY

From bite-sized insights to deep dives on healing, NOTES ON THERAPY is where mind meets meaning.

As therapists, staying informed about mental health is essential. Sharing current research and raising awareness helps to reduce stigma and makes mental health support more accessible and relatable in everyday life. Check out the blog posts below for the latest in psychology and mental health.

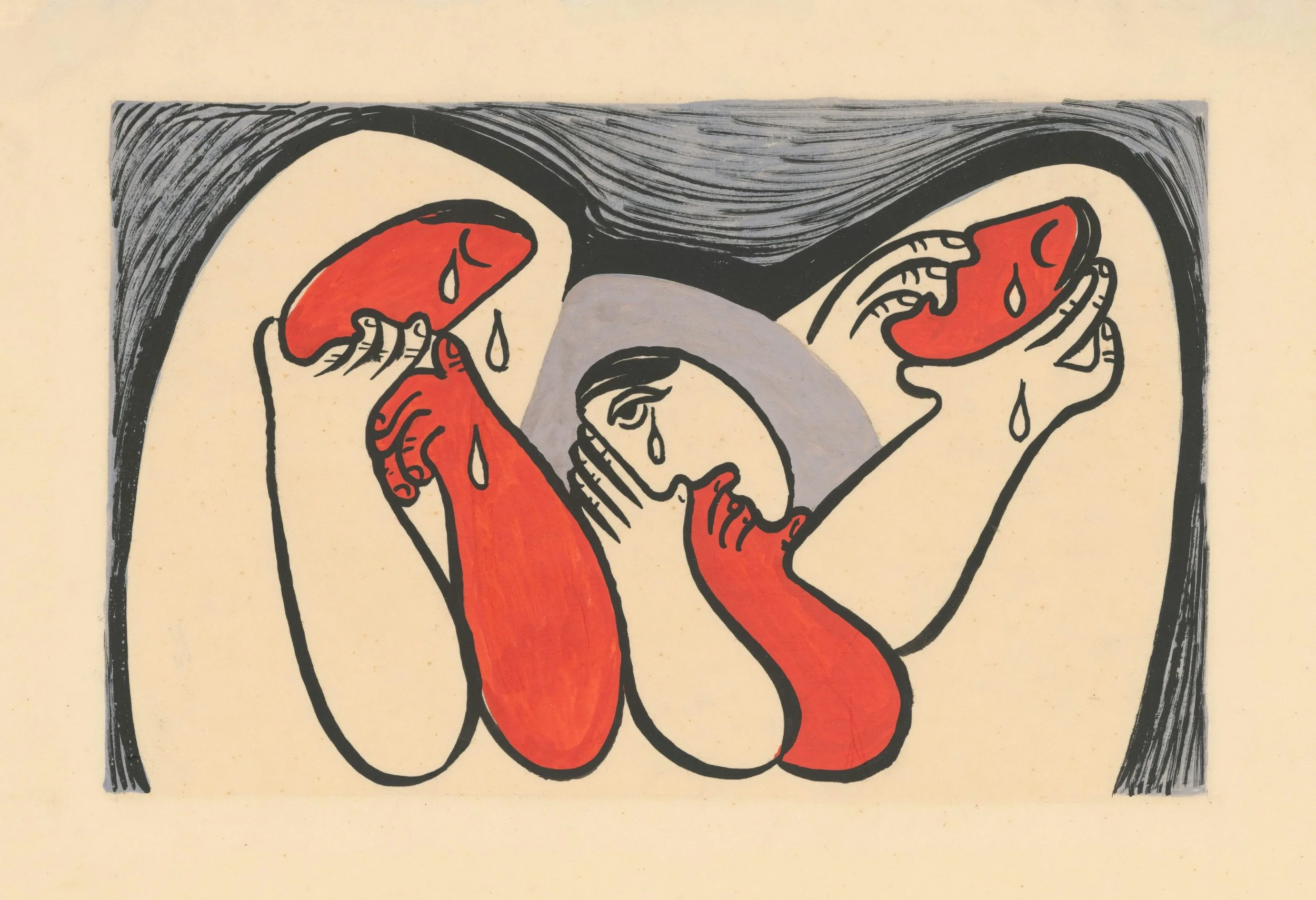

Why Do We Cry?

The Science and Psychology of Emotional Tears

The Science and Psychology of Emotional Tears

Written by Emma Nagle,, LCSW | May 22, 2025

Research suggests that crying offers a range of benefits for both mental and physical well-being.

Crying is a deeply human behavior. It is both biologically driven and emotionally meaningful. A quiet signal that something within us is asking to be felt, witnessed and let go. While often misunderstood as a sign of weakness, emotional tears serve an essential regulatory function in the body and mind. We don’t just cry from sadness; we cry from relief, empathy, beauty, overwhelm, and connection.

In this article, we explore the science behind why we cry: how emotional tears differ from other types of tears, what they communicate in the nervous system, and why this uniquely human act plays a vital role in mental and emotional health.

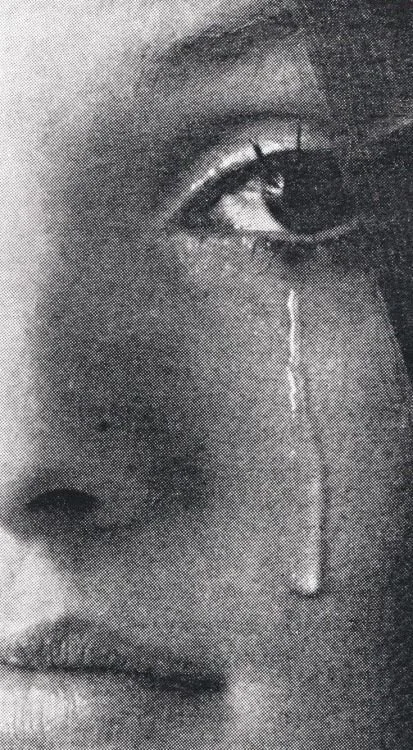

To start, we need to acknowledge that not all tears are the same. Like most other animals, us humans produce basal tears constantly. These are the type that keep our eyes lubricated and healthy. Then there are reflexive tears, which protect the eyes from irritants like smoke or onion fumes. But emotional tears are uniquely human. These are the tears that rise from feelings and carry meaning. And, they may do more for our mental and physical health than we realize.

Beneath the surface of a simple tear drop lies a complex system of neurobiological and emotional regulation. When we cry, we engage the body’s natural calming mechanisms mainly through the parasympathetic nervous system, which helps shift us out of “fight, flight, freeze, fawn” and into a state of rest and restoration. This process can reduce anxiety, relieve built-up tension, and promote a feeling of calm.

Emotional tears also help us process and express intense feelings such as grief, frustration, fear, or even joy, that might otherwise remain locked in the body. As the tears fall, we may feel a sense of emotional release, a lightening, or a softening in the chest.

Biochemically, crying can stimulate the release of endorphins and oxytocin.

These neurochemicals are associated not only with soothing pain, but with enhancing mood, and promoting a sense of connection and calm. This may be why we often feel calmer or sleepy after a good cry, even if nothing externally has changed.

Emotional tears are chemically different.

Emotional tears differ from the ones we shed when chopping onions or clearing dust from our eyes (reflexive). They contain higher levels of stress-related hormones, including cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). Some researchers believe that this chemical composition suggests a form of emotional detoxification, meaning that when we cry under stress or sadness, our bodies may literally be releasing what we no longer need to hold.

CRYING serves as a

release valve

for both the body

& the mind.

Other researchers continue to debate the idea that crying "detoxifies" the body.

The argument here is that the amount of stress hormone released through tears is too small to produce measurable physiological effects. Some point to the relief we feel after crying stems more from the nervous system’s shift into parasympathetic regulation than from literal chemical elimination. A 2020 study found that although crying helped regulate physiological responses such as maintaining stable breathing and heart rate, it did not lower cortisol levels compared to neutral or non-crying conditions. In short, the biology is real, but the full story of why crying feels good may be more about regulation than removal. We may owe more to nervous system regulation, endorphin release, and human connection than to an actual chemical cleansing. The science is still settling on this theory.

Crying also plays an important role in social connection.

And not just in modern emotional relationships, but in our evolutionary wiring. Emotional tears are specific to humans, and researchers believe they evolved as a nonverbal form of communication, cues and help to inform us when support is needed, thus prompting caregiving responses.

Interestingly, as we get older, we tend to cry more in response to empathy. Crying in response to witnessing someone else's emotional experience, especially moments of deep connection, vulnerability, altruism, sacrifice, reunion, or acts of compassion is often referred to as empathic crying. These moments are linked to the emotion often described as being moved, and tend to become more meaningful as we mature. This shift may reflect how our emotional and moral understanding deepens over time, making us more sensitive to human connection and shared experience.

Furthermore, in times of mourning or loss, crying becomes a shared language of grief. It is an outward expression of internal pain that invites empathy and communal healing. Across cultures, tears serve as both a personal release and a public signal, reminding us that grief is not meant to be carried in isolation. When met with empathy, crying not only helps us feel seen, which fosters closeness, deepens trust and also strengthens the invisible threads that hold us together as humans.

“Tears are the silent language of grief.”

— Voltaire

what to keep in mind

Not all crying feels relieving, and not every person experiences these effects in the same way. The benefits of crying can depend on many factors: personality traits, emotional regulation skills, cultural and gender norms, and the context in which tears are expressed.

When crying happens in a safe, supportive environment, it often leads to comfort and connection. But when tears are met with shame, judgment, or isolation, their healing power may feel out of reach and create negative associations.

While the science is still evolving, the theory of emotional detoxication supports the idea that crying is not just symbolic. We understand that the act of crying serves a biological function in helping us regulate internal stress. Tears offer not just emotional relief, but also a subtle physiological reset and opportunity to communicate. Rather than viewing tears as a loss of control, we might begin to see them as the body’s built-in way of recalibrating and restoring balance back to homeostasis.

In summary,

Crying can bring relief, deepen connection, and give shape to feelings that words alone cannot hold. It’s not a weakness, but a language—one that bridges the biology of our bodies with the emotion of our lived experience. To cry is to be human. And sometimes, it’s also how we heal.

*If crying becomes overwhelming, constant, or interferes with daily functioning, it may signal deeper emotional distress. In these cases, seeking professional support can provide the tools and care needed to process what’s beneath the surface.

References:

Bylsma, L. M., & Gračanin, A. (2021). A clinical practice review of crying research. Psychotherapy, 58(4), 492–502. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000395

Gračanin, A., Kardum, I., & Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M. (2019). Why do we cry? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(2), 234–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721419827526

Gračanin, A., Bylsma, L. M., & Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M. (2014). Is crying a self-soothing behavior? Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 502. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00502

Sharman, L. S., Dingle, G. A., Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M., & Vanman, E. J. (2020). Using crying to cope: Physiological responses to stress following tears of sadness. Emotion, 20(7), 1279–1291. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000633